Met. 1.548-52 – Daphne’s Transformation

Vix prece finita torpor gravis occupat artus;

mollia cinguntur tenui praecordia libro;

in frondem crines, in ramos bracchia crescunt;

pes modo tam velox pigris radicibus haeret;

ora cacumen habet; remanet nitor unus in illa.

Scarcely is her prayer finished when a heavy numbness grips her limps;

her soft breast is wreathed in tender bark;

her hair turns to leaves and her arms grow into branches;

her foot, which just before was quick, clings to the ground with sluggish roots;

her face becomes the treetop; her elegance is the only part of her that remains.

(Met. 1.548-52)

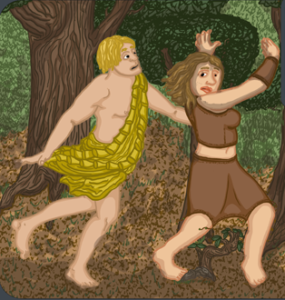

Well, there – those of you who have been baying for girls turning into trees, here’s a girl turning into a tree! Daphne is arguably the girl-turning-into-a-tree of the Metamorphoses. She is one of Ovid’s most iconic characters, and is generally the figure most people who haven’t read the poem will already know. This notoriety is probably due in large part to her popularity in visual art, especially during the Rennaissance. Just as Daphne is an iconic character, Bernini’s sculpture of ‘Apollo and Daphne’ is iconic among depictions of the myth. It’s housed today in the Galleria Borghese of Rome. The Galleria has a number of Bernini sculptures and works by other artists that are drawn from episodes of the Metamorphoses (definitely worth paying a visit if yo

u have a chance). ‘Apollo and Daphne’ are among the most visited, however, as tourists flock to see a work they likely know from photos or cast copies. Indeed, Bernini’s sculpture has itself become an object of imitation, as Jean-Étienne Liotard’s 1736 painting shows. I swear it is only a massive coincidence that my own artistic nod to Bernini, on the last page, used the same angle as his!

u have a chance). ‘Apollo and Daphne’ are among the most visited, however, as tourists flock to see a work they likely know from photos or cast copies. Indeed, Bernini’s sculpture has itself become an object of imitation, as Jean-Étienne Liotard’s 1736 painting shows. I swear it is only a massive coincidence that my own artistic nod to Bernini, on the last page, used the same angle as his!

I actually had to think hard about how to depict Daphne’s transformation. Bernini’s sculpture, like many artistic depictions of the transformation, actually mashes together several points of action into one moment. In the Latin lines above, you can see that Apollo is nowhere mentioned during the transformation. Bernini has the god’s left hand caressing Daphne’s stomach (might be hard to see in the angles above); in Ovid, conversely, he doesn’t actually touch her until she is almost in full tree mode (that’s the next page). Also, Bernini’s Daphne is naked, because of course she is *eye role*. In my reading, Apollo has not quite caught her yet when she transforms (although he is breathing down her neck: Met. 1.542). I decided to have Apollo actually trip and be left a little behind (on page 55), just so I could justify the time it takes Daphne to pray (I also interpolated the presence of Peneus’ waters *bad Charlotte, no!* but then again so did Liotard…) Finally, for this page, I wanted the transformation to take centre stage, and I think it definitely does that. The angle and composition are my own, but are also a nod to Ovid’s sequence of describing the parts of her transformation; he went breasts to feet, so I decided on the top-down view, with a focus on her head in the centre, just as her head caps the transformation in the poem. All in all, I’m happy with it, but perhaps I could have done better. What do you think? Did I capture your vision of Daphne’s dendromorphia? Or did I miss something you think is crucial? What’s your favourite depiction of Apollo and Daphne in visual art? Let me know down in the comments!

This is very impressive, Charlotte. The attention to detail in your interpretation of the text is penetrating and incisive. I also appreciate your sense of humor, in particular in your depiction of Daphne’s struggles with her nasty suitors and pushy father. Please use more words like “dendromorphia.” The precision in your vocabulary contributes to the whimsical tone of the piece in a self-consciously erudite manner. No other representation could ever replace Bernini’s sculpture in my internal visualization of the scene, but you have done an excellent job of reinterpreting the story with fine attention to the humanity of the figures in the midst of their transformations.

Thanks for saying, I really appreciate that! I will definitely endeavour to use more words like “dendromorphia” 😉 I don’t expect to rival Bernini, of course, but I do hope the depiction fit with your vision and with the rest of the story’s pages.

Oh yes, I thought your depiction was quite satisfactory. I think that your “added value” as an artist is in embracing the iconography of the myth but transposing it into the twenty-first century in a way that incorporates contemporary themes and media. You are able to enhance much of the subtlety of the original Ovid and bring it to life for modern audiences.