Met. 1.32-37 – Moulding the Globe

SIC UBI DEPOSITAM QUISQUIS FUIT ILLE DEORUM

CONGERIEM SECUIT SECTAMQUE IN MEMBRA REDEGIT,

PRINCIPIO TERRAM, NE NON AEQUALIS AB OMNI

PARTE FORET, MAGNI SPECIEM GLOMERAVIT IN ORBIS.

TUM FRETA DIFFUNDI RAPIDISQUE TUMESCERE VENTIS

IUSSIT ET AMBITAE CIRCUMDARE LITORA TERRAE

WHEN THIS WAS DONE SO, WHICHEVER OF THE GODS IT WAS

DIVIDED THE MASS AND REORDERED THE PIECES INTO PARTS [OF THE WHOLE],

IN FIRST PLACE, THE EARTH, SO THAT IT WOULD BE EQUAL ON ALL SIDES

HE ROLLED INTO THE SHAPE OF A GREAT GLOBE.

THEN HE ORDERED THE SEAS TO BE POURED OUT AND TO TOSS IN THE SWIFT WINDS

AND TO ENCOMPASS THE SHORES OF THE LANDS

Aaaaaaand we’re back! Sorry for the downtime, everyone. Check out the post “Site Downtime”, under “Recent Posts” on the right, to read more about it and my future plans.

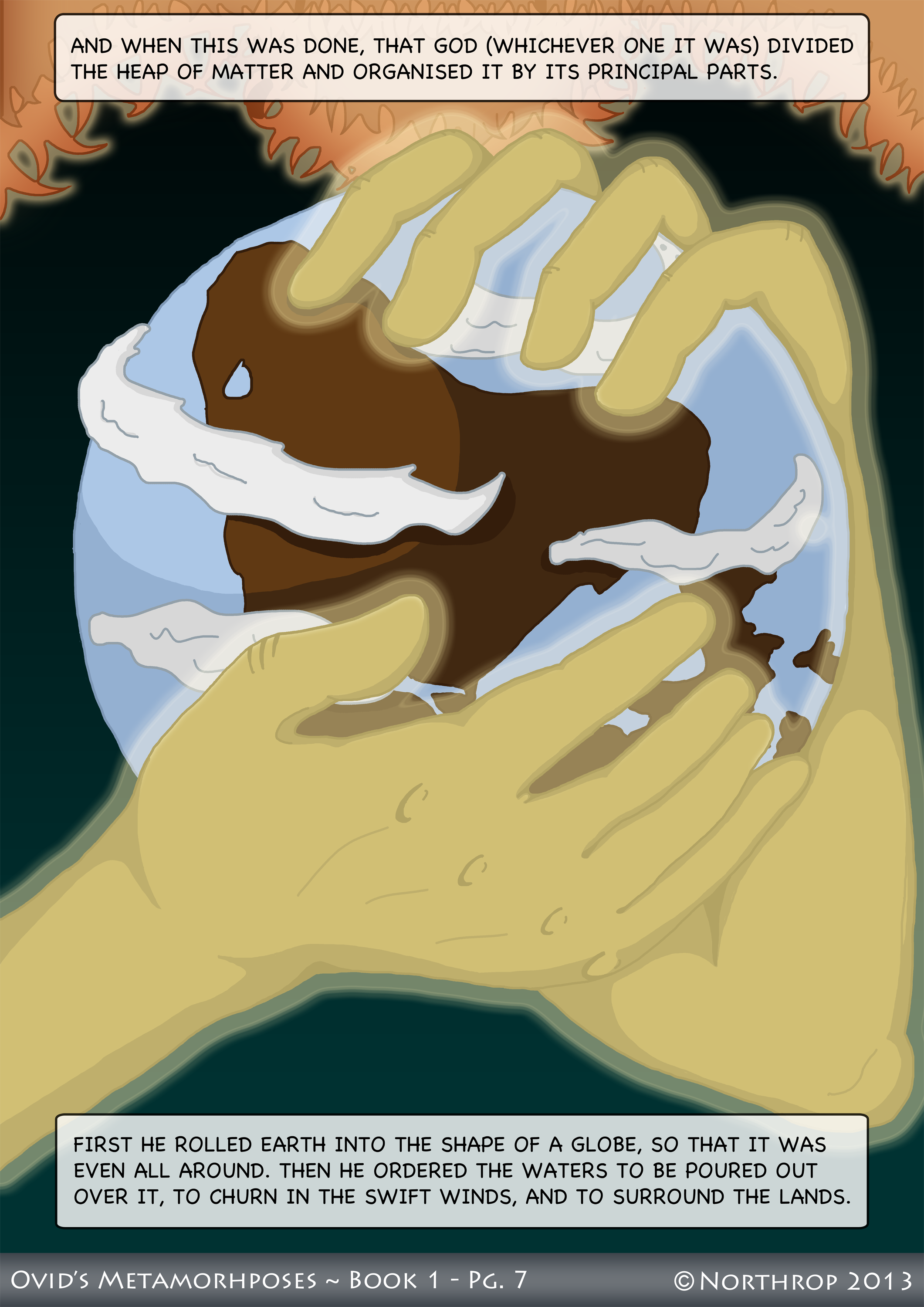

Here we get to the interesting part about geography*. Yes, that is a globe, and yes people in the ancient world knew the Earth was round (gasp!). Poets and philosophers alike make reference to it; by Ovid’s day, it was common to refer to “the globe” of lands (Vergil did it, so it must be cool). The Latin is very clear (perhaps clearer than the English): the word orbis (root of our word “orb”) means either “round” or “spherical”. While this could refer to disk as well, the word glomere removes the ambiguity. Glomere means “to roll into a ball” and quite often refers to rolling up a ball of yarn. Weaving and textile work constitute frequent imagery in Ovid’s poem. Here, they accentuate the delicate and artistic work of the creator of the world.

The creator’s identity remains a mystery, and will indeed not be revealed at any point. He is a disembodied agent of metamorphosis, transforming Chaos with an artist’s touch. His identity is a hot debate, even today. Medieval Christians, who read the Metamorphoses quite a lot (considering its very un-Christian values), saw the god of Genesis in Ovid’s demiurge. Alessandro Barchiesi points this out in his comment on the “whichever of the gods it was” line, which leaves open a myriad of possibilities. There are, of course, striking similarities with the first book of the Bible (just wait until the flood…), and it may even be possible that Ovid read Genesis. Ingo Gildenhard, at a recent presentation to the University of Cambridge, argued Ovid did have access to a Greek translation. It is very possible that it ended up being one of his sources. However, if this is the case, Ovid apparently had little special reverence for the Biblical account (indeed, at a different presentation, I heard Gildenhard refer to the Metamorphoses itself as the “anti-Bible”). It enters his poem as another flavouring to an already well-spiced stew of different versions of the creation myth. This is Ovid’s technique as an author. He doesn’t invent whole stories, but arranges a collage of myths that nevertheless come out to be something entirely new. He takes a Chaotic story-telling tradition and makes something whole and beautiful out of it. In this light, Ovid himself is as true an identity for the creator as anyone.

My version of the creator will, from here on out, only be glimpsed by his hands. I really like the reading of him that sees him as an artist of the cosmos, and so I wanted to emphasise the tactile relationship he has with his creation. Like an artist, he gently and carefully works his material into just the right shape. However, in what will be a common fault in my project, this depiction loses something of the original poetry. While, yes, he is an artist, who is sometimes described as giving a ‘hands-on’ treatment to the cosmos, he also uses other means of creation. As Stephen Wheeler, in his article, “Imago Mundi: Another View of the Creation in Ovid’s Metamorphoses“, points out, the creator likes to bark orders. There is a repetition over the next few lines of the word “iussit” (“he ordered”). Wheeler sees this as another artistic motif, pointing out its connection to the work of Hephaestus on the Shield of Achilles in Iliad 18, where Homer repeats the words “ποίησε” and “ἐτίθει” (“he made” and “he set”). It is part of Wheeler’s rather interesting suggestion that the entire cosmogony is what is called an ekphrasis, or a description in poetry of a work of art. The Shield of Achilles definitely is one, and commonly these ekphraseis describe physical objects (armour, statues, cups etc.); the idea is that Ovid wants the whole cosmos to be a work of art treated in an ekphrasis. This is a salient idea, and I must say I am attracted to it. However, it does not describe the whole situation here. The ordering is also very martial, and echoes the martial language used in the fighting of the elements when they were still part of Chaos. Therefore, a double meaning can be drawn from this simple repeated verb: on the one hand, the demiurge is an artist, creating his piece with authority. On the other, he is a commander, whipping the disorderly elements (which have been personified to a degree thus far) into line. This second interpretation certainly squares with line 20: “this fight some god or better nature broke up”. I do not mean to say either theory is better than the other. This is the beautiful thing about reading; it’s so subjective. You may have just done a double-take. Let me explain: some people feel that there has to be a “right” (objective) answer to interpreting poetry, but this is not the case. There can be multiple valid readings, each addressing a different reader’s sensibilities. I really like the interpretation of his as an artist, but you might disagree. At any rate, both interpretations have parts of the text that support them. It takes a skilled poet to weave disparate meanings together, but in the end, it produces a work that can be enjoyed both by those who like their god to be an artist, and those who like him to be a commander-in-chief.

So, which do you prefer?

*If you don’t think geography is interesting, then I am very sorry: please be patient; nudity and violence are coming soon, I promise.

Discussion ¬