Met. 1.369-83 – Instructions for saving the world

Nulla mora est; adeunt pariter Cephisidas undas

ut nondum liquidas, sic iam vada nota secantes.

inde ubi libatos inroravere liquores

vestibus et capiti, flectunt vestigia sanctae

ad delubra deae, quorum fastigia turpi

pallebant musco stabantque sine ignibus arae.

ut templi tetigere gradus procumbit uterque

pronus humi gelidoque pavens dedit oscula saxo;

atque ita ‘si precibus’ dixerunt ‘numina iustis

victa remollescunt, si flectitur ira deorum,

dic, Themi, qua generis damnum reparabile nostri

arte sit et mersis fer opem, mitissima, rebus.’

mota dea est sortemque dedit: ‘discedite templo

et velate caput cinctasque resolvite vestes

ossaque post tergum magnae iactate parentis.’

Without delay, they proceed side-by-side to the waters of Cephisus

which, while they were not flowing freely, were still making their way along their usual course.

From there they took some water and sprinkled it

on their clothes and heads, and they turned back

to the temple of the holy goddess, whose pediments were

covered in nasty moss, and whose altars stood without flames.

As they arrived at the temple steps, they both lay

flat on their faces and kissed the ground and cold stone with trembling lips;

and so they said, “If the deities might be won over and soften their anger against just men,

if the anger of the gods can be deflected,

Tell us, Themis, by what art could the destruction of our race be reversed,

and bring help for our drowned society, o goddess most gentle.”

The goddess was moved and gave them this prophesy: “leave the temple;

cover your heads and loosen your robes,

and toss the bones of your great mother over your back.”

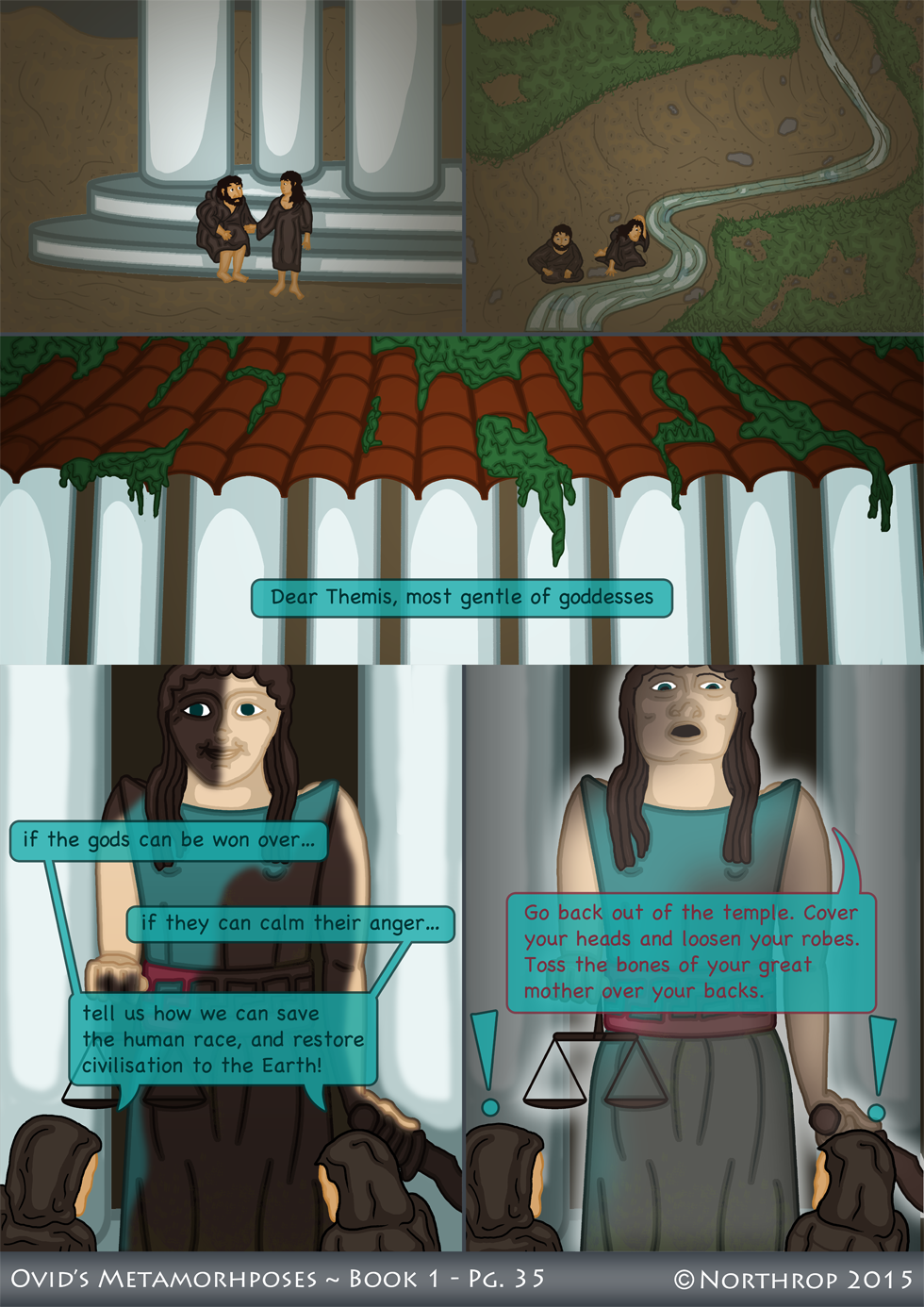

Oh geez…. you know when working on something drags on so long that finishing it becomes a slog? Well, that happened with this page; sorry it took so long! It’s done now, and I am fairly okay with how it turned out. I tried to depict a bronze statue, whose paint had been partially washed away by the flood. I did this, in part for realism, and in part to satisfy both classicists (who know statues were painted), and non-classicists (who might have mistaken it for a giant, un-blinking woman, instead of a statue). I’m not sure how well I pulled it off, and it took a while to get this bit done, but I am happy that I at least learned some new illustration techniques for this page. I think when the next episode starts, I might experiment with switching up my approach to line-drawing and colouring; we shall see…

In terms of the poem, this page is fairly straight forward. Deucalion and Pyrrha perform a ritual purification in the nearby Cephisus river and then pray to Themis. Their prayer is fairly standard, considering the extraordinary circumstances. Often in Latin, poetic prayers contain a lot of conditionals (if the gods are happy with me; if there is mercy in heaven; etc.). This might seem… rude… to a modern reader, but it reflects the tit-for-tat relationship polytheists* had with their gods. The gods receive sacrifice and obedience, and in return they cough up favours to the pious. Luckily, Deucalion and Pyrrha happen to be extra pious, and the fulfillment of their prayer just so happens to have been prophesied by Jupiter and the Fates before the flood. So, they get a lucky break… that is, if they can figure out what the hell the voices are telling them to do…

Tune in (hopefully) next week to find out!

* “Polytheist” is a more academically correct term for “pagan”; that word comes from the Latin “paganus”, which refers to a hick or country bumkin. The word became associated with worshipping more than one god in late antiquity, when the “urbane” Christians became prominent in the cities, while the yokels in the countryside still worshipped the old pantheon.

Discussion ¬