Met. 1.481-7 – Daphne’s Wish

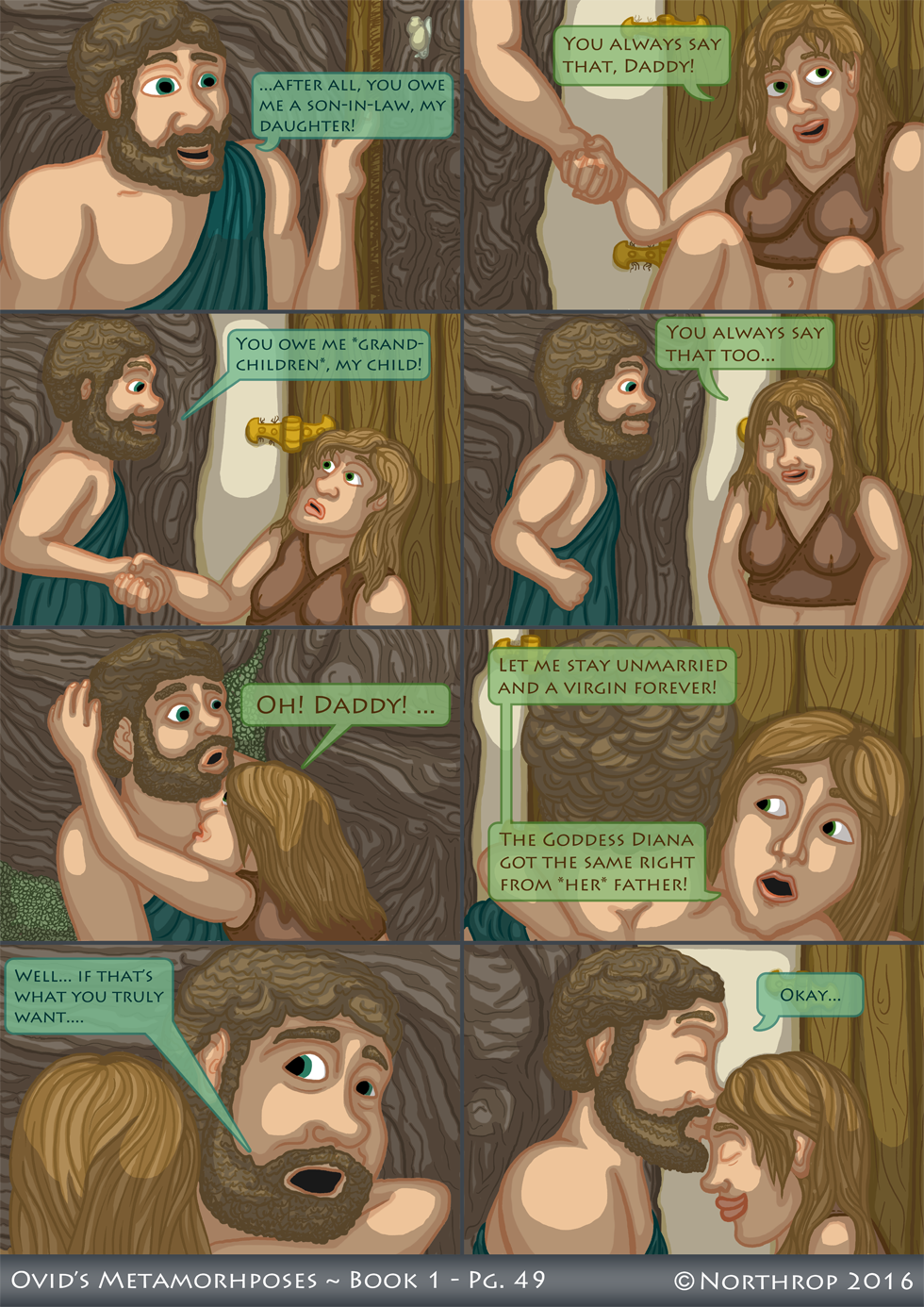

saepe pater dixit “generum mihi, filia, debes”;

saepe pater dixit “debes mihi, nata, nepotes.”

illa velut crimen taedas exosa iugales

pulchra verecundo suffunditur ora rubore,

inque patris blandis haerens cervice lacertis

“da mihi perpetua, genitor carissime” dixit,

virginitate frui; dedit hoc pater ante Dianae.”

often her father said, “you owe me a son-in-law, my daughter”;

often her father said, “you owe me grandchildren, my child.”

She, hating marriage torches as if they were a crime,

covered her face in a modest blush,

and hanging on her father’s neck with her fawning arms

she said “dearest father, let me

enjoy virginity forever; her father once gave this [gift/right] to Diana.”

Now we see what was being set up with the last page. If you’ll recall, I emphasised the fact that the last page featured only dialogue that I had made up. Ovid suggest such scenes in the text, but I chose to invent a specific set of interactions that could be depicted in comic form and set up this very important conversation.

Daphne asks for eternal virginity and – perhaps surprisingly – gets her father to agree. I just want to take a minute to discuss this word “virginity”, because it is a recurring theme in the Metamorphoses, and it doesn’t mean quite what it means today. Today, we think of “virgins” as being those who have never had sex. In the ancient mindset, it was a more expansive concept than that. Abstinence is implied by virginity, but it also a term strongly connected to marriage. “Virgins” is the term for unmarried girls and sexually inexperienced girls, and usually implies youth, although not always. There is an equivalent notion for boys, but the emphasis on sexual abstinence is lessened, and there is no directly corresponding word. Daphne is part of a set of mythological characters that I and other Ovidians usually refer to as “militant virgins”. They are not only unmarried, but also hate sex, men and women who have sex with men (except their parents). They might be anachronistically compared with the movement for “Lesbian Separatism” in the 1970s, although there are many important philosophical differences between the two groups (in addition to the fact that, you know, the militant virgins of mythology are fictional). Whether or not militant virgins are inherently open to homosexual relationships is a matter for debate, and probably varies from author to author (for what it’s worth, Ovid seems to imply that Callisto might have a lesbian relationship in Book 2). We’ll see this character type repeat regularly throughout the Metamorphoses. The characters that fit this type, in addition to hating heterosexuality, are often hunters and have an affinity for the woods. They are also invariably engaged with the cult* of the goddess Diana to some degree.

Diana (know as Artemis in Greek; also called Selene, Luna and other cultic names) is the sister of Apollo, goddess of the Moon, the hunt, female maturation and childbirth. It is, thus, not surprising to see Daphne reference her here. Afterall, Daphne is a girl coming of age, and she is therefore under the special protection of the goddess. Moreover, what Daphne said about Diana is true: her father really gave her the right to be a virgin forever. Specifically, Daphne’s words seem to echo Diana herself. Jeffry Wills (1990) pointed out the textual echo here in the Metamorphoses to the Hymn to Artemis (Hymn 3) by Callimachus, a 4th-3rd century BC poet working at the Library of Alexandria in Egypt. Listen to what the Callimachean Artemis says:

ἄρχμενοι, ὡς ὅτε πατρὸς ἐφεζομένη γονάτεσσι

παῖς ἔτι κουρίζουσα τάδε προσέειπε γονῆα

“δός μοι παρθενίην αἰώνιον, ἄππα, φυλάσσειν,

(Callimachus, Hymn 3 To Artemis, ll. 4-6)

Beginning just when she, sitting on her father’s knee,

still a growing child, said these things to her sire,

“let me keep my virginity forever, daddy”

Artemis’ speech goes on, but this line that is really salient for us here in the Metamorphoses. It’s the same idea that Daphne communicates to her father, but the wording is what makes it striking. Ovid’s Daphne begins “da mihi”, an echo of the Greek “δός μοι”, which the Callimachean Artemis repeats five times in her speech to her father. At the end, her father nods his assent while she tries to play with his beard. It’s a rather sweet hymn, in which Artemis asks for each facet of her cult in turn, essentially establishing a major religious movement as a child playing bouncy-horse. Ovid is not only aware of his reference, he wants his reader to realise it too. Daphne’s line, “Diana’s father once gave her this [right/gift]”, is what we call an “Alexandrian footnote”, named after the same library where Callimachus did his writing. An Alexandrian footnote is a knowing hint in the text, that points the reader back to the author’s source material. Thus, Daphne hopes to emulate Artemis/Diana, right down to the way she entreats her father for permission to never marry. The irony is that while Artemis/Diana got the right from her father, Zeus/Jupiter, Daphne can’t hope to emulate her totally. Such an emulation would be bordering on hubristic, attempting to rival the goddess herself (remember my discussion of “emulation” under page 47). This brings me to a study by Helen King (2002); King points out that Artemis is distinct from her followers because she is immune to the hardships that plague the girls she oversees. Artemis was thought to help menstruating girls, for instance, despite the fact that Artemis herself does not menstruate. She is able to help precisely because she is immune. Artemis herself says something similar in the same Callimachean Hymn; at ll. 19-25, she points out that she should help women in childbirth, although her own mother did not feel pain in birth. Likewise, as a virgin, Artemis is free of the pains of sex and marriage, although prepares her followers for marriage all the same. Her followers cannot hope to be like her, and this means that they will suffer, according to their lot in life. Artemis helps as best she can, but ultimately must leave them to their fates.

* I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating: “cult”, in ancient religion, does NOT mean the same thing as our modern tabloid sense of “fringe religion”. Ancient cults are the specific subsets of polytheistic religion that are focused on one diety in particular. Each diety had their own cult, or even several, which would have been usually state-sponsored and furnished with a dedicated priesthood and specific social and regional functions. Diana’s cult was female-oriented, and patronised pubescent girls and women in childbirth, among other functions.

I just discovered this comic due to it being published on the AWOL newsletter. It’s nice to see that you haven’t abandoned it completely. I was just thinking that now that graphic novels are so popular it would be time to turn some Latin classics into comic books: first of all Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

You should probably stop publishing this on the Web and start to think of it as a project that can bring money and that you could get a publisher for.

I’m pretty sure I could find a publisher for it in Italy once the comic and the notes are translated into Italian. If I was sure you were going to finish this I could even start to translate it right now.

The format with the comic on the top half of the page and the original text with translation and notes on the bottom half could work out very well, making the book enjoyable as a fun read, but also useful as a tool for hight school students.