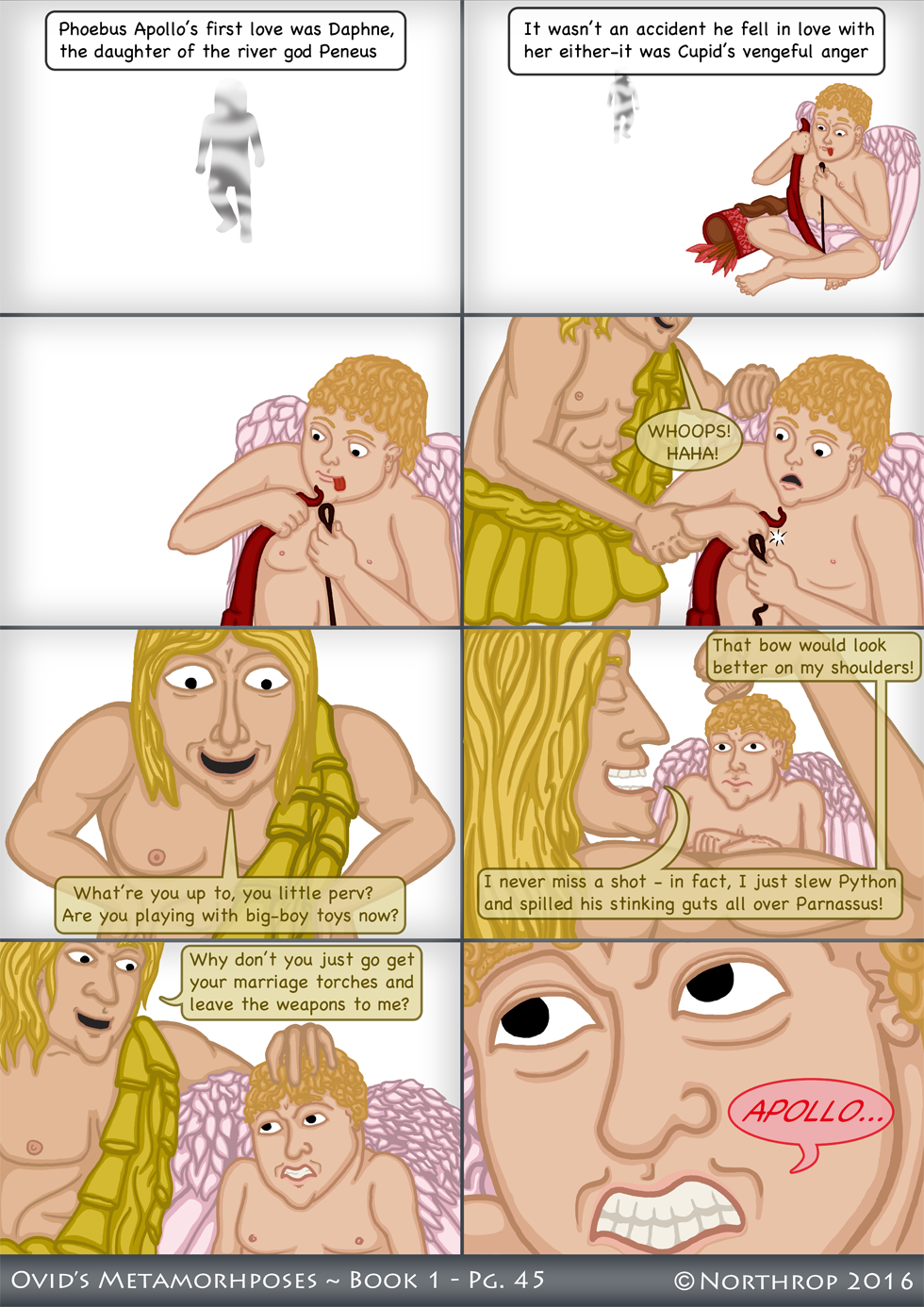

Met. 1.452-65

Primus amor Phoebi Daphne Peneia, quem non

fors ignara dedit, sed saeva Cupidinis ira.

Delius hunc, nuper victa serpente superbus,

viderat adducto flectentem cornua nervo

“quid”que “tibi, lascive puer, cum fortibus armis?”

dixerat; “ista decent umeros gestamina nostros,

qui dare certa ferae, dare vulnera possumus hosti,

qui modo pestifero tot iugera ventre prementem

stravimus innumeris tumidum Pythona sagittis.

tu face nescioquos esto contentus amores

inritare tua, nec laudes adsere nostras.”

(Met. 1.452-62)

The first love of Phoebus [Apollo] was Daphne, daughter of Peneus, whom

blind chance did not give him, but the savage anger of Cupid.

The Delian [Apollo], flush from his recent victory over Python,

had seen him [Cupid] bending his bow to the taunt string

and had said, “what are you doing with high-powered weaponry, you lusty little boy?

That piece is worthy of our* shoulders,

which [we use] to give sure wounds to beasts and sure wounds to enemies,

which [we used] just now to lay out huge Python, his pestilent gore covering so much of the mountain peaks,

with innumerable arrows.

You go be content to stir up some love or other with your marriage torches**,

and don’t try to claim praises due to us.”

Whoah, wait… monster fights, then a love story???? What gives, Ovid? Seriously, though, this turn might be a bit surprising. Up until now, we’ve been getting a heavy dose of cosmology and natural philosophy. Lycaon and Deucalion/Pyrrha were arguably proper ‘myths’, but even they tied into the cosmological elements. Now, we get an introduction to what will become a signature theme in the Metamorphoses: erotica. This should not be taken as an indication that the poem is about to become pornography (although certain segments verge on the pornographic and fetishistic). This is “erotica” in the purest sense: stories inspired by Eros (ERO-tica), called Cupid by the Romans and most modern English-speakers as well.

Dedicated fans of Ovid (of whom there seem to have been quite a few in Augustan Rome) will actually recognise that Ovid is returning to form here. If you think aaaaaaaaall the way back to line 2 (on page 1 of this comic), you’ll remember that Ovid said the gods had changed his project, in addition to all the other changes he referred to. It comes off as a strange comment if you aren’t familiar with Ovid’s early work. Ingo Gildenhard and Andrew Zissos (2000) have a lovely article that explains this line in terms of Ovid’s poetic career. In his first collection of poems, the Amores (“loves”), Ovid opens the collection with a poem about Cupid messing with his work:

Arma gravi numero violentaque bella parabam

edere, materia conveniente modis.

par erat inferior versus – risisse Cupido

dicitur atque unum surripuisse pedem.

Arms in heavy number and violent wars I was preparing

to write about, matters suited to my metre.

The second line was equal to the first – Cupid,

it is said, laughed and stole one foot.***

(Ovid, Amores 1.1.1-4)

This is going to take some unpacking, because these lines are an extended joke about the metre of Latin poetry. There are many different metres, but Ovid is referring to two here: the epic metre (dactylic hexametre), which has six ‘feet’ (units of syllables) on each line; and the elegiac metre, whose lines alternate between hexametres (six feet) and pentametres (five feet). Epic is appropriate for war, heroes and monsters. Elegiac can incompasse everything from funeral poetry to (more commonly in Augustan times) love songs. The different themes connected to these two metres make them emblematic of different genres. Therefore, the joke is that Ovid wanted to write an epic about “arms” (none too subtly, this is the first word of the most famous Latin epic, Vergil’s Aeneid) when Cupid stole a “foot” off his second line, changing the metre to elegiac (six and five foot lines), and thus forcing him to write about “loves” instead, in order to fit the metre to the genre. It is taken as Ovid saying that he cannot bring himself to write about “heavy” (n.b. “gravi” in line 1) subjects, but instead wants to focus on Cupid and eroticisim. So, when Ovid does write an epic (the Metamorphoses uses hexametres in each line), it seems he rather sheepishly pushed Cupid back from the beginning.

Nevertheless, when Cupid does enter the Metamorphoses, he enters it in a big way. The “primus amor” (“first love”) at the beginning of line 452 seems to be an important signal that the poem is about to shift gears. I sometimes wonder if Ovid originally meant to start here, but decided to go back and add the cosmological elements later (this is very difficult to prove however; maybe it will be the topic of a future research project, but for now it’s just wild speculation). At any rate, Ovid is not about to leave Cupid out as a character, considering that god was his ‘first’ character all the way back at the beginning of his career. The line, ‘primus amor’ also signals to his readers that Ovid has not really turned to “arms in heavy number and violent wars”. He may be writing an epic, but it is an epic on his terms, in which Cupid is an important figure. As Barchiesi (2007: pp. 206) points out, the fact that it is Cupid and Apollo who are quarrelling is significant. Apollo is traditionally the patron deity of epic; Cupid is the patron of erotic elegy. Ovid is combining the subject of elegy (love) with the metre and style of epic. Therefore, Cupid and Apollo represent the inherent conflict of the poem’s genre. Is it epic? Is it erotic elegy? Well, it’s both, and the resolution of the fight will show just how complicated this combination can become. We’ll have to wait for the next page in order to see where this fight leads, though.

* I know I should have mentioned this before, but it’s not uncommon for poetic characters to refer to themselves in the plural (we, us, our). Apollo isn’t just suddenly channeling Queen Victoria here.

** If you’re confused about what torches have to do with weddings, it’s useful to know that the Roman wedding ceremony included a nighttime procession from the bride’s house to the groom’s house (where he was waiting to receive her), which was lit by torchlight. The torches included in this ceremony became synonymous with marriage itself by Ovid’s day.

*** Ovid goes on to argue with Cupid about the stolen foot, but to no avail.

Discussion ¬